Third molar teeth (commonly referred to as wisdom teeth) consist of the mandibular and maxillary third molars; they usually appear between the ages of 17 and 25. They are called wisdom teeth because usually they come in when a person is between age 17 and 25 or older—old enough to have supposedly gained some wisdom. Most adults have four wisdom teeth, but it is possible to have more or fewer. Absence of one or more wisdom teeth is an example of hypodontia. Any extra teeth are referred to as supernumerary teeth. Wisdom teeth commonly affect other teeth as they develop - becoming impacted or "coming in sideways." They are often extracted when this occurs.

Etymology of "wisdom teeth"

They are generally thought to be called wisdom teeth because they appear so late—much later than the other teeth, at an age where people are presumably wiser than as a child, when the other teeth erupt. The English wisdom tooth is derived from Latin dens sapientiae. The same root is shared by numerous other languages. There exists a Dutch folk etymology which states that the Dutch word for wisdom tooth verstandskies is derived from "far-standing" (ver-staand) molar, and that mistranslations of the Dutch word (in which verstand translates to wisdom) are the root for corresponding words in other European languages.

Impaction

Impacted wisdom teeth fall into one of several categories. Mesioangular impaction is the most common form (44%), and means the tooth is angled forward, towards the front of the mouth. Vertical impaction (38%) occurs when the formed tooth does not erupt fully through the gum line. Distoangular impaction (6%) means the tooth is angled backward, towards the rear of the mouth. And finally, Horizontal impaction (3%) is the least common form, which occurs when the tooth is angled fully ninety degrees forward, growing into the roots of the second molar.

Typically distoangular impactions are the easiest to extract in the maxilla and most difficult to extract in the mandible, while mesioangular impactions are the most difficult to extract in the maxilla and easiest to extract in the mandible. Frequently, a fully erupted upper wisdom tooth requires bone removal if the tooth does not yield easily to forceps or elevators. Failure to remove distal or buccal bone while removing one of these teeth can cause the entire maxillary tuberosity to be fractured off and thereby the tearing out the floor of the maxillary sinus.

Impacted wisdom teeth may also be categorized on whether they are still completely encased in the jawbone. If it is completely encased in the jawbone, it is a bony impaction. If the wisdom tooth has erupted out of the jawbone but not through the gumline, it is called a soft tissue impaction. Sometimes the wisdom tooth fails to erupt completely through the gum bed and the gum at the back of the wisdom tooth extends over the biting surface, forming a soft tissue flap or lid around the tooth called an operculum. Teeth covered by an operculum can be difficult to clean with a toothbrush. Additional cleaning techniques can include using a needle-less plastic syringe to vigorously wash the tooth with moderately pressured water or to softly wash it with hydrogen peroxide.

However, debris and bacteria can easily accumulate under an operculum, which may cause pericoronitis, a common infection problem in young adults with partial impactions that is often exacerbated by occlusion with opposing 3rd or 2nd molars. Common symptoms include a swelling and redness of the gum around the eruption site, difficulty in opening the mouth, a bad odor or taste in the mouth, and pain in the general area which may also run down the entire lower jaw or possibly the neck. Untreated pericoronitis can progress to a much more severe infection.

If the operculum does not disappear, recommended treatment is extraction of the wisdom tooth. An alternative treatment involving removal of the operculum, called operculectomy, has been advocated. There is a high risk of permanent or temporary numbness of the tongue due to damage of the nerve with this treatment and it is no longer recommended as a standard treatment in oral surgery.

The oldest known impacted wisdom tooth belonged to a European woman of the Magdalenian period (18,000 - 10,000 BP)

Extraction

under local anaesthetics.

Wisdom teeth are extracted for two general reasons: either the wisdom teeth have already become impacted, or the wisdom teeth could potentially become problematic if not extracted. Potential problems caused by the presence of properly grown-in wisdom teeth include infections caused by food particles easily trapped in the jaw area behind the wisdom teeth where regular brushing and flossing is difficult and ineffective. Such infections may be frequent, and cause considerable pain and medical danger. Other reasons wisdom teeth are removed include misalignment which rubs up against the tongue or cheek causing pain, potential crowding or malocclusion of the remaining teeth (a result of there being not enough room on the jaw/ in the mouth),as well as orthodontics.

A panoramic x-ray (aka "panorex") is the best x-ray to view wisdom teeth and diagnose problems.

Post-extraction problems

There are several problems that might occur after the extraction(s) have been completed. Some of these problems are unavoidable and natural, while others are under the control of the patient. The suggestions contained in the sections below are general guidelines that a patient will be expected to abide by, but the patient should follow all directions that are given by the surgeon in addition to the following guidelines. Above all, the patient must not disregard the given instructions; doing so is extremely dangerous and could result in any number of problems ranging in severity from being merely inconvenient (dry socket) to potentially life-threatening (serious infection of the extraction sites).

Bleeding and oozing

Bleeding and oozing is inevitable and should be expected to last up to three days (although by day three it should be less noticeable). Rinsing the mouth during this period is counter-productive, as the bleeding stops when the blood forms clots at the extraction sites, and rinsing out the mouth will most likely dislodge the clots. The end result will be a delay in healing time and a prolonged period of bleeding. However, after about 24 hours post-surgery, it is best to rinse with lukewarm saltwater to promote healing. This should be done twice a day until the swelling goes down and every 4–6 hours after that for at least a week. Gauze pads should be placed at the extraction sites, and then should be bitten down on with firm and even pressure. This will help to stop the bleeding, but should not be overdone as it is possible to irritate the extraction sites and prolong the bleeding or remove the clot. The bleeding should decrease gradually and noticeably upon changing the gauze. If the bleeding lasts for more than a day without decreasing despite having followed the surgeon's directions, the surgeon should be contacted as soon as possible. This is not supposed to happen under normal circumstances and signals that a serious problem is present. A wet tea bag can replace the gauze pads.Tannic acid contained in tea can help reduce the bleeding.

Due to the blood clots that form in the exposed sockets as well as the abundant bacterial flora in the mouth, an offensive smell may be noticeable a short time after surgery. The persistent odor often is accompanied by an equally rancid-tasting fluid seeping from the wounds. These symptoms will diminish over an indefinite amount of time, although one to two weeks is normal. While not a cause for great concern, a post-operative appointment with one's surgeon seven to ten days after surgery is highly recommended to make sure that the healing process has no complications and that the wounds are relatively clean. If infection does enter the socket, a qualified dental professional can gently plunge a plastic syringe (without the hypodermic needle) full of a mixture of equal parts hydrogen peroxide and water or chlorohexidine gluconate which also comes in the form of a mouth wash into the sockets to remove any food or bacteria that may collect in the back of the mouth. This is less likely if the person has his/her wisdom teeth removed at an early age.

Dry socket

A dry socket is not an infection; it is the event where the blood clots at an extraction site are dislodged, fall out prematurely, or fail to form. It is still not known how they form or why they form. In some cases, this is beyond the control of the patient. However, in other cases this happens because the patient has disregarded the instructions given by the surgeon. Smoking, blowing one's nose, spitting, or drinking with a straw in disregard to the surgeon's instructions can cause this, along with other activities that change the pressure inside of the mouth, such as sneezing or playing a musical instrument. The risk of developing a dry socket is greater in smokers, if the patient has had a previous dry socket, in the lower jaw, and following complicated extractions. The extraction site will become irritated and painful, due to inflammation of the bone lining the tooth socket (osteitis). The symptoms are made worse when food debris is trapped in the tooth socket. The patient should contact their surgeon if they suspect that they have a case of dry socket. The surgeon may elect to clean the socket under local anesthetic to cause another blood clot to form or prescribe medication in topical form (e.g. Alvogel) to apply to the affected site. A non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) such as ibuprofen may be prescribed by the surgeon for pain relief. Generally dry sockets are self limiting and heal in a couple of weeks without treatment.

Swelling

Swelling should not be confused with dry socket, although painful swelling should be expected and is a sign that the healing process is progressing normally. There is no general duration for this problem; the severity and duration of the swelling vary from case to case. The instructions the surgeon will tell the patient for how long they should expect swelling to last, including when to expect the swelling to peak and when the swelling will start to subside. If the swelling does not begin to subside when it is supposed to, the patient should contact his or her surgeon immediately. While the swelling will generally not disappear completely for several days after it peaks, swelling that does not begin to subside or gets worse may be an indication of infection. Swelling that re-appears after a few weeks is an indication of infection caused by a bone or tooth fragment still in the wound and should be treated immediately.

Nerve injury

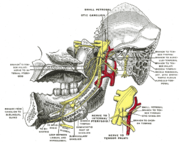

This is primarily an issue with extraction of third molars, but can occur with the extraction of any tooth should the nerve be in close proximity to the surgical site. Two nerves are typically of concern and are found in duplicate (on the left and right side):

- The inferior alveolar nerve, which enters the mandible at the mandibular foramen and exits the mandible at the sides of the chin from the mental foramen. This nerve supplies sensation to the lower teeth on the right or left half of the dental arch, as well as sense of touch to the right or left half of the chin and lower lip.

- The lingual nerve, which branches off the mandibular branches of the trigeminal nerve and courses just inside the jaw bone, entering the tongue and supplying sense of touch and taste to the right and left half of the anterior 2/3 of the tongue as well as the lingual gingiva (i.e. the gums on the inside surface of the dental arch).

Such injuries can occur while lifting teeth (typically the inferior alveolar) but are most commonly caused by inadvertent damage with a surgical drill. Such injuries are rare and are usually temporary. Depending on the type of injury (i.e. Seddon classification: neuropraxia, axonotmesis, and neurotmesis) they can be prolonged or permanent.

Treatment controversy

Preventive removal of the third molars is a common practice in developed countries despite the lack of scientific data to support this practice. In 2006, the Cochrane Collaboration published a systematic review of randomized controlled trials in order to evaluate the effect of preventive removal of asymptomatic wisdom teeth. The authors found no evidence to either support or refute this practice. There was reliable evidence showing that preventative removal did not reduce or prevent late incisor crowding. The authors of the review suggested that the number of surgical procedures could be reduced by 60% or more. This study, however, was published in the Journal of Phytology and is not accredited by many peer review organizations.

Likewise, ClinicalEvidence published a summary, largely based on the Cochrane review, that concluded prophylactic extraction is "likely to be ineffective or harmful." The website offered the following details:

While it is clear that symptomatic impacted wisdom teeth should be surgically removed, it appears that extracting asymptomatic, disease-free wisdom teeth is not advisable due to the risk of damage to the inferior alveolar nerve.

Some non-RCT evidence suggests that the extraction of the asymptomatic tooth may be beneficial if caries are present in the adjacent second molar, or if periodontal pockets are present distal to the second molar.

Studies showed that dentists graduated from different countries or even from different dental schools in one country, may have different clinical decisions regarding third molar removal for the same clinical condition. For example, dentists graduated from Israeli dental schools may recommend more often for the removal of asymptomatic impacted third molar than dentists graduated from Latin-American or Eastern European dental schools.

In the U.K., the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (an authority which appraises the cost-effectiveness of treatments for the National Health Service) has recommended that impacted wisdom teeth that are free from disease should not be operated on. Conversely, in the U.S., the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (the professional organization representing oral and maxillofacial surgeons in the United States) recommends that all wisdom teeth should be removed at an early age as a prophylactic measure. This would suggest that recommendations regarding the removal of third molars vary widely from country to country, depending on the stakeholders involved.

Vestigiality and variation

Wisdom teeth are vestigial third molars that human ancestors used to help in grinding down plant tissue. The common postulation is that the skulls of human ancestors had larger jaws with more teeth, which were possibly used to help chew down foliage to compensate for a lack of ability to efficiently digest the cellulose that makes up a plant cell wall. As human diets changed, smaller jaws gradually evolved, yet the third molars, or "wisdom teeth", still commonly develop in human mouths.

Other findings suggest that a given culture's diet is a larger factor than genetics in the development of jaw size during human development (and, consequently, the space available for wisdom teeth).

Different human populations differ greatly in the percentage of the population which form wisdom teeth. Agenesis of wisdom teeth ranges from 0.2% in Bantu speakers to nearly 100% in indigenous Mexicans. The difference is related to the PAX9 gene (and perhaps other genes).

No comments:

Post a Comment